Author Archives: Keith Weiner

An Allegation of Plagiarism

An allegation of plagiarism, which is a serious charge, has been made against me.

Writing about my paper (The Unadulterated Gold Standard, Part III), Hugo Salinas Price, a respected thinker in the gold and silver community, published an article on Christmas Eve (Keith Weiner plagiarizes).

He states: “The intellectual work of Prof. Antal E. Fekete, Dean of the New Austrian School of Economics, has been plagiarized by Keith Weiner…”

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, an act of plagiarism means to: “v. Take (the work or an idea of someone else) and pass it off as one’s own.”

Mr. Salinas Price continues: “Not one word of recognition is afforded to the author [emphasis added], by Weiner.”

This implies that Professor Fekete is the author of my paper.

Mr. Salinas Price does not quote either from Professor Fekete’s paper or my own nor does he provide evidence.

Even if Mr. Salinas Price means that I do not credit Professor Fekete as my teacher in monetary science, this charge is also untrue. Until Professor Fekete awarded my degree, my bio stated I was “a student at the New Austrian School of Economics, working on his PhD under Professor Antal Fekete”. Now, it says “he has his PhD from the New Austrian School of Economics”.

In numerous papers, from the first I published (Fractional Reserve Banking) to my dissertation (A Free Market for Goods, Services, and Money) to the most recent on Dec. 22 (Reflections Over 2012), I credit Professor Fekete and cite his papers. This includes my submission to the Wolfson Economics Prize (Gold Bonds to Avert Financial Armageddon).

I clearly, openly, and repeatedly state that I am an Objectivist, which means that I credit Ayn Rand for my philosophy including ethics and my view of capitalism. I also acknowledge Professor Fekete as integral to the development of my thinking in monetary science. The ideas of both Rand and Fekete are obvious in my writings.

I hope this statement clarifies this issue and demonstrates that I take what I write seriously. However, under the circumstances, because he has presented not a shred of evidence to support his inflammatory charge of plagiarism, I think Mr. Salinas Price should apologize.

Meanwhile, the world faces a grave threat. The monetary system is moving inexorably towards collapse (When Gold Backardation Becomes Permanent). Those who love civilization have serious work to do.

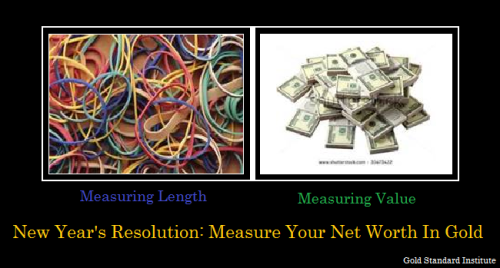

New Year’s Resolution

Reflections Over 2012

The last workweek of the year is complete. Beers were had with friends yesterday, Friday evening. The final shopping trip to the mall was completed today, followed by a good meal with my wife. Now I find myself in a reflective mood, and this is a perfect time to reflect on what an incredible year it was.

Around this time last year, I began writing my dissertation. I knew what I wanted to prove: that a free market is driven by arbitrage to the benefit of all participants, and that the same principle applies in money and credit as it does to the production of food or computer chips. I had no idea that I would not be done until I had typed 32,000 words onto 110 pages!

How many things in life are like that? “If I knew then what I know now!” Every path you take in life has its price. You take what you want and you pay for it. But often, you don’t know the price in advance. After I sold DiamondWare, I spent a few months of reflection and soul-searching about this.

Anyways, in March of this year, I went to the New Austrian School while it was still practically winter in Munich (at least to someone with the “thin” blood of an Arizona resident!) to lecture, and discuss my dissertation. Based on discussions I had while there, I agreed to establish the Gold Standard Institute USA. It was around then that I started to mutter, “so much time, so little to do…” (sorry, sarcasm) to anyone who would listen.

Shortly after that, both the Basel Committee and the domestic regulators in the US announced proposed changes to the rules that would allow banks to gold as a “zero risk weighted” or “Tier 1” asset. Other than a few gold bugs, who got excited about higher gold prices (which have so far not materialized), few paid heed to the broader consequences. John Butler of Amphora Capital was one notable exception. This is a step towards the inevitable gold standard.

Also this year, I had a chance to record some lectures I gave in Phoenix. In the future, I plan to do more in the video format. Aside from being a lot of fun, I think it can reach a different audience and even reach the same audience in a different way as compared with the written word. Partly as a result of these videos, I was invited to give a keynote at the Gold Symposium in Sydney and a one-day economics seminar for Golden Renaissance in October, but I am getting out of chronological order.

In September, it was back to Europe for the next lectures at the New Austrian School and the award ceremony for my doctorate! Back in 1990, when I dropped out of computer science school to get started writing code, I never thought I would be back to school for anything, much less a graduate degree, much less in economics! But the journey that I had begun after selling DiamondWare weeks before the markets began to collapse; starting to read about economics had come full circle.

I want to thank again Professor Antal Fekete for his numerous writings about monetary science. Reading them started me on this path, which led to my travel to Szombathely, Hungary one cold and cloudy winter, to meet him and begin my study under him. Professor Fekete’s ideas form the core of my own thinking about money and credit today.

In many of my earlier papers, I cited his papers and I plan to continue to use his papers as references in my own when they are specifically germane. Thus I want to take this opportunity to acknowledge my intellectual debt to him again. It is impossible for me to imagine what the development of my thinking in economics would have been without my having studied Fekete, as it is similarly impossible for me to imagine my personal, business, and philosophical development without Ayn Rand. Astute readers will see the influence of Rand on everything I say and do, and Fekete on everything I say in economics.

To paraphrase Isaac Newton (who may have been paraphrasing the logician and theologian John of Salisbury): it is by standing on the shoulders of giants that I am able to see farther and undertake my own work. I am dedicating this phase of my life to helping to bring the world forward (not backward!) to the gold standard. The gold standard is, well, it’s the gold standard of monetary systems.

I also want to thank Professor Juan Rallo of King Juan Carlos University, Madrid who was the other examiner of my dissertation.

After Munich, it was on to Neuberg An Der Mürz for the wedding of my colleague Thomas Bachheimer, president of the Gold Standard Institute in Europe. Neuberg is a classic alpine Austrian village, with flowers in front of all the houses—and a church built in the 13th century. Due to its clear, rather than stained, glass windows, it was a light and airy place and very impressive. Congratulations again Thomas. It alone, if not driving on roads without speed limits in a Mercedes, would have made the trip worthwhile!

After returning, I launched Monetary Metals with my business partner Stuart Clapick. This is the other part of my effort to bring the world forward to gold. I will be writing more about Monetary in the near future.

And finally, to complete the year, I received news yesterday. I am an angel investor, who invests money (and sometimes time) in high-tech startups. My first career was in software and I still love it. I have a small portfolio of Arizona-based early stage companies (and one in Dunedin, New Zealand). Two of my portfolio companies, Post.Bid.Ship and Serious Integrated, won the Arizona Innovation Challenge. Arizona awarded each of them a not-inconsiderable amount of money. While I will likely benefit from these grants financially, I find that I have mixed feelings. I wish the world would not grant to government the power to take taxes from everyone and then attempt to pick winners by giving out subsidies! I am not given that choice, though hopefully my work (and the work of many others) will help people discover the simple and yet elusive concept of freedom. In the meantime, I wish everyone a Merry Christmas and happy New Year! 2013 promises to be very exciting, or perhaps “interesting” as in the old Chinese proverb.

Unadulterated Gold Standard, Part III

KeithGram: The “Crash JP Morgan” Campaign

Unadulterated Gold Standard, Part II

Unadulterated Gold Standard, Part I

Open Letter to Hugo Salinas Price

Keith Weiner

President, Gold Standard Institute USA

Weiner (dot) Keith (at) Gmail (dot) Com

Nov 7, 2012

Re: Open Letter to Hugo Salinas Price

Dear Mr. Price:

I read your piece: “On the Use of Gold Coins as Money” (http://www.plata.com.mx/mplata/articulos/articlesFilt.asp?fiidarticulo=196). I think you ask the right question. This is the elephant in the room. Why do gold and silver not circulate?

I love your analogy of the Swiss asserting that they will “allow” gold to have a monetary role, this being like “re-hydrating water.” It is not within the power of foolish governments either to imbue water with wetness, or gold with moneyness.

Gold is already money. It is the commodity with the tightest bid-ask spread. It is the commodity with the highest ratio of inventories divided by annual mine production (stocks to flows). And it is the commodity whose marginal utility does not decline. These statements are as true for gold today as they were under the gold standard 100 years ago.

Let’s look at marginal utility. I think you hit the nail on the head: people will pay in anything but gold, if it is possible to do so. People prefer to keep gold, and this preference has nothing to do with the amount of gold they or anyone has.

What is the practical effect of this? There are two things that individuals could theoretically do with their gold. The first is that they could hoard it. It does not produce a yield, and it does not finance production. But if there is no other option available this is what people must do.

So long as people are taking gold from circulation to hoard it, then the circulation mechanism is broken. An equilibrium is reached when all the gold is in private hoards.

People could also save gold. They could buy bonds (or deposit it in a bank that will buy bonds). The enterprises that borrow the gold will use it to finance production. Gold will continue to circulate.

You make a very important point that is underappreciated, if not lost, in the dialog today. A piece of paper is a promise. A gold coin is a tangible good. I love your analogy to the engagement ring. If a man gives a woman a contract that says the wedding will be on such-and-such date that is not equivalent to a gold ring!

You make the case that if people have no other means of making payment, they will pay in gold and silver. You acknowledge this could take a long time. Let me propose another way to go forward to the gold standard.

There is one thing that will motivate people to place their gold at risk, and give up possession (temporarily).

Interest – paid in gold.

Interest can lure the gold and silver out of hoards and to the twin tasks at hand: recapitalizing the financial system and financing production. Then it is just a matter of time. First bondholders and then suppliers are paid in gold. Gold begins to circulate.

If one has a gold income then one is free to accept gold liabilities, such as leases and employee wages. For the firs time since 1913, the monetary system would be on a good path.

But without interest, without the promise of a gain to tempt gold hoarders to part with their metal, they will, as you say, find any alternative currency with which to pay. The world will continue on its inexorable march towards permanent gold backwardation.

That is what I think you and I are both working to try to prevent!

Regards,

Keith Weiner

Gold in the Core of the Banking System

I originally published this piece in The Gold Standard, the journal of the Gold Standard Institute. I reproduce it here because people have been asking about it.

On June 4, Department of the Treasury Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve System (the Fed), and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) issued a joint notice of proposed rulemaking (http://www.fdic.gov/news/board/2012/2012-06-12_notice_dis-d.pdf). On June 18, the FDIC issued a Financial Institution letter with the stated goal of updating banking regulations to implement changes made by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Dodd-Frank Act (http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2012/fil12027.html).

Both documents propose a positive for gold. Under the proposed new regulations, gold is to have a zero risk weighting, like dollar cash and US Treasury bonds. This will allows banks to own gold on more advantageous terms, as they won’t need to tie up other capital just to support their gold position.

One can only imagine what stress the banks must be under if the regulators and the Fed are willing to consider this extreme measure! Do they not have sufficient other assets? Or is the issue that most other assets are either garbage or already encumbered?

This segues into a theme that I plan to discuss more in the future. The re-monetization may not take place by passage of a monolithic law, but in increments. This change, and not even in law but in regulation—not even considered by Congress but by unelected bureaucrats—is an important step towards a gold-based monetary system. For the first time in many decades, banks can hold actual gold as part of the backing of their deposits, and not just as a trading position. Regardless that this may be a “hail Mary” pass thrown in desperation and lack of anything else that the government would prefer, I think it heralds a sea change and a highly important milestone in our fight to return to a sound monetary system!

In 1933, when President Roosevelt outlawed gold ownership for US citizens, he removed the only real competition of US Treasury bonds. Those investors who wanted absolute safety of their capital were deprived of the only risk-free financial asset. So they were herded into government bonds, like cattle to slaughter (thus driving down the rate of interest and crushing the debtors).

Now, gold may be a viable competitor to the bond (assuming this proposed rule goes into effect) in the banking system. While individuals can and do buy and hoard gold today, there have been significant disincentives for banks to own gold. Now, what is arguably the biggest obstacle is being removed.

What will the impact be? Obviously, additional demand will come into the gold market. So the price will go up. But The Gold Standard Institute is not about speculating on the dollar price of gold. From a monetary perspective, there are two interesting angles to consider regarding this development.

With competition from gold, some of the demand is taken away from US Treasury bonds. Could this mean falling bond prices, and hence rising interest rates? The wildcard is the Fed and its perpetual purchases of bonds. I don’t think anyone in his right mind would buy bonds in this world, except as a speculation on the next action of the Fed, and the speculators (the survivors) are adept at figuring out what they will do next.

Another interesting thought is that to the extent they switch out of the Ponzi scheme of bonds that are never repaid, only “rolled” into gold, the banks will become more sound. As gold is the one asset whose dollar price can rise without any particular limit, it may be a matter of time before banks are substantially recapitalized simply due to the rising price of gold held outright as an asset on their balance sheets.

This is exciting! I hope every reader goes out tonight and has a glass of wine to toast “to the return of gold!”